On Artful Intelligence

Happy New Year, Maker Educators

I’d like to share what I’m thinking about in the new year.

I predict that sometime in the future researchers will look back on this AI era and ask some tough questions. One might be: why did trillions of dollars go into developing artificial intelligence and so little into developing new learning models for young humans and increasing their capacity to do things? In other words, why did we overinvest in machine learning to create artificial intelligence and underinvest in the deep learning necessary for the young to become more skillful at solving problems and making decisions?

If CES 2026 is any indication, we have a tech industry trying to do things for us and they’re not very good at it, according to Gizmodo’s Kyle Barr in his piece, “Humanoid Robots Are Here… and Embarrassingly Bad at Being Our Servants.” He writes:

The lingering question is whether any of the robots will be capable of doing anything useful.

Forget about what robots can do for now. Isaac Asimov predicted in 1963 that by 2014 “robots will be neither common nor very good.” He also said that society “will have few routine jobs that cannot be done better by some machine than by any human being.”

The lucky few who can be involved in creative work of any sort will be the true elite of mankind, for they alone will do more than serve a machine.

—Isaac Asimov

What are we doing as a society to prioritize developing young people who can learn to do creative work? Will they be able to make AI serve them rather than the other way around? Will they become better at making decisions?

While robots and AI are well-funded for the future, our backward-looking education system is underfunded and unable to adapt to what is coming. It’s a factory model based on standardization and rote memorization. Passive learning is the dominant mode, not constructionist learning that is active and experiential. A decade or more of EdTech startups have promised to automate learning but they have left us with a child sitting in a chair staring at a screen. AI too often offers the same empty promise.

Here’s Brendan Foody, a 22-year-old billionaire founder and CEO of the AI company, Mercor, which is using experts to train AI. On the podcast, “Conversations with Tyler,” Foody said:

“I think education is one of the things I’m most excited about, where a good heuristic is if everyone has Sal Khan as their personal tutor, available 24-7 to teach them whatever topic they want to learn, it’ll be that it’s much easier to motivate themselves. It’s much better access to information, much better ways of explaining that information, and that’ll be profoundly impactful.”

— From Conversations with Tyler - Brendan Foody on “Teaching AI and the Future of Knowledge Work,” Jan 7, 2026

Foody, who was a Thiel Fellow and skipped college, is evidently self-directed and motivated to achieve. Not all students are. Are they able to learn on their own and take advantage of Sal Kahn as an AI tutor? Or will they just watch YouTube or TikTok to entertain themselves?

What we don’t value enough in education is the role of teachers, coaches and counselors. Educators don’t necessarily need to be strong subject-matter experts but they need to be exceptional learners who can share their learning process with students. They need to be expert in working with youth. More and more, teachers will see their roles less defined by subject matter and more by a set of skills that are critical to being a good coach who can help students grow and thrive.

Regardless of whether AI is involved, we need “humans in the loop” who are responsible for developing other capable humans. This human connection is essential in education and training — people learn best from others — but it conflicts with the business goals of AI to replace humans, or reduce the need for them. We need to value the people who are really good at developing human potential as much as we value engineers who build algorithmic learning machines.

David Weitzner’s new 2025 book— Thinking Like a Human: The Power of Your Mind in the Age of AI (Amazon link) argues that the key to navigating the age of AI is not to compete with machines, but to embrace uniquely human cognitive abilities, which he calls “artful intelligence.” He writes:

As we race headlong into a future where we outsource all our problem-solving to artificial intelligence, the greatest threat is not superintelligent machinery, but too much trust in Big Tech and not enough trust in the power of our own minds.

Weitzner spoke about his book on a recent Quillette podcast and he’s written an article for the site, titled “Algorithmic Supremacists and AI Hype," which I recommend reading. “As AI hype is taking up all the air space,” he writes, “there is little room for public consideration of the recent cavalcade of mind-blowing findings on natural intelligence.”

I call the opposite of algorithmic supremacy “artful thinking.” It’s thinking with our body… our hands, eyes, ears, hearts, guts, and brains. It’s using the environment we are in to support us. It’s engaging our bodies in physical spaces to think through real-world actions. We have so many underutilised cognitive resources at our disposal. I call this BEAM (body, environment, action, mind).

Algorithmic supremacists want to keep us isolated. When I attend industry conferences I keep hearing about an agent-to-agent future, where even the internet as we know it disappears, and all communication is between our personal bots. Meanwhile, underfunded and under-platformed scientists are discovering the massive untapped potential in our physical bodies, natural intelligence, and the magic that happens when we come together, human-to-human, not agent-to-agent. Writing is thinking. Socialising is thinking. Taking action is thinking. What else will science teach us about ourselves in the coming years? And will AI let the message reach us?

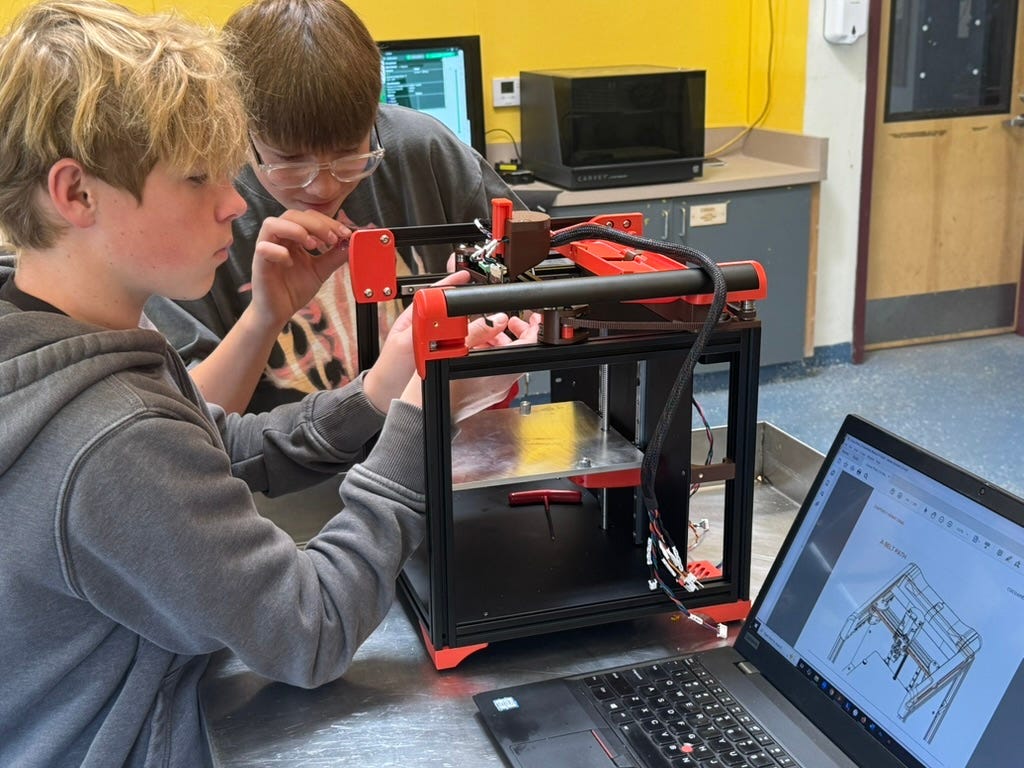

I like Weitzner’s idea of artful intelligence, one that is acquired through practice and interactions with others, engaging both mind and body. That’s what Maker Education is about—a holistic model of embodied learning that encourages the learner to produce creative work using whatever tools are at their disposal. As the saying goes, which often refers to craftsmanship, the tool is only as good as its user. Said another way, AI will only be as good as the human using it, and that’s a person who can also decide not to use it.