Making a Meaningful Makerspace

After a pandemic-induced pause, Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh finds interest returns for professional development related to school makerspaces

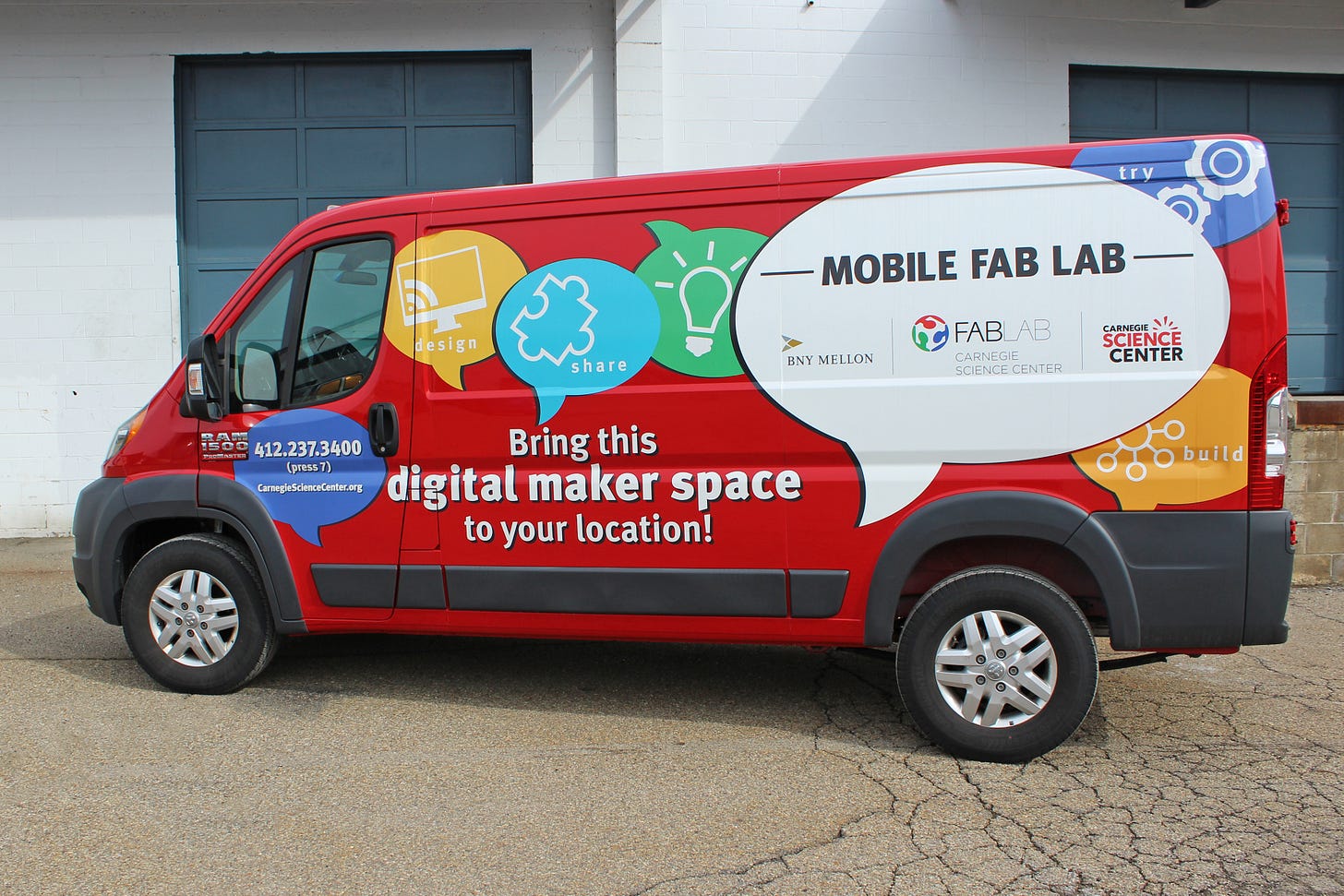

Jon Doctorick is the Director of STEM outreach programs at the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Science Center has a Fab Lab and runs a number of programs for students who come to visit. Carnegie Science Center also has a program called Makers in Motion, in which n outfitted van can visit schools and bring making and the equipment for making to the classroom. There are different professional development programs around STEM and Maker education at Carnegie Science Center, and there is new interest in these programs post-Covid.

In this discussion with Jon, we talk about developing makerspaces in schools and operating a mobile makerspace. But the pandemic put on hold the kind of professional development that Carnegie Science Center offered to schools. Now, there’s new interest in learning how to define a mission for a makerspace that includes hands-on activities but also to integrates into language arts and history as well as STEM. It’s not just about having cool technology but it’s about “making makers.”

Dale: The question really is, especially post covid, how do we restart makerspaces in schools?

There's a feeling, if nothing else, that some of the people who started makerspaces in schools have perhaps retired or moved on. We have new people sometimes getting assigned responsibility for a makerspace and they go: “oh, what do I do?”

Jon: That’s what we here at Fab Lab CSE have dubbed “found makerspaces.” It's a really large part of how we have completely revitalized our professional development post Covid.

Dale: So why don't we start with some background on yourself.

Jon: I've been with Carnegie Science Center here in Pittsburgh for about 14 years. I began part-time outreach, just taking the classroom kits into schools, doing the programs on the weekends, whenever it fit my graduate school schedule. It turned into a full-time gig. I'm a reformed high school English teacher, but I just fell in love with what we do here.

What pushed me out of teaching was standardized testing during my student teaching in my first two years of teaching. I wanted to be teaching kids about color theory and Great Gatsby and learning how to write a paper and instead, it was— learn these vocabulary words for this standardized test. I was like, I can't do this.

At the same time, I was doing part-time work here and I just fell in love with this style of education because even though we're referred to as an informal science institution, it's pretty formalized sometimes. I'm part of the STEM Ed department. Schools are leaning on us now to provide science curriculum that they can't.

I ended up in a full-time job doing outreach, taking the assemblies in schools, blowing things up for kids.

A Mobile Makerspace

Our outreach has a very large reach. In a normal year, which we're getting to be this year, we can see in excess of a hundred thousand kids with our programs. We're all over the place on any given day. In 2015 the person who was the senior director of STEM ed at the time, Jason Brown, who is now our CEO here, he saw an opportunity to apply for a very large grant to bring a makerspace to Carnegie Science Center, so a stationary makerspace, which is still here. Then we also received a grant for a traveling mobile makerspace as well. We began with a large trailer but it just doesn't work very well in an area like Pittsburgh, which is very hilly. It just was not playing well with Pittsburgh. We readjusted our model, made it a van-based mobile Fab Lab. Everywhere that would book us to come in, they can provide us a space inside the school. A van has worked really well for us.

Dale: It's a bit like like a bookmobile that you're delivering something and you leave it behind.

Jon: Exactly, yeah.

Dale: Some of the early mobile makerspaces were meant to be mobile workshops and they were cramped and they don't work that well for serving many people.

Jon: Six months out of the year, it’s cold and rainy. You can't get the kids outside. So we broke that model down and actually all of the equipment that was in the trailer, we can fit it in a full-size van. We have a lift, so we can take laser cutters, 3D printers, vinyl cutters, all of the computers.

We recreate the space in the school, which to me is actually better because it helps the staff and the administration visualize what a makerspace could look like and how it can function in their school versus having to come out to the trailer. We started that process in 2015.

We were the recipient of what was pretty typical, a very expensive hardware dump. What are you going to do with all this hardware? When you give that to an institution like us, we are able to figure out what to do with it. It took us about two years. We really have hit a stride with shifting our mission originally from what are the cool things you're making versus our mission now encompasses we're making makers. We're making kids and adults that are comfortable coming into this space. And even if they don't make anything successful, it doesn't matter.

It's the process of coming into this space, the skills they learn and how they can apply what they learn to the rest of their life. So we found our mark with that, doing programming and professional development onsite and offsite. Around 2017-2018, we had a couple-year head start on a lot of other science museums and a lot of them began reaching out, even libraries. They wanted to know how do you do this?

There was a big market for not just dumping hardware on an organization and saying good luck, but providing the hardware and also the training. Deep training, curriculum associated with it, and a long term partnership where we can actually mesh our partners together so we all can learn from one another.

We've actually installed makerspaces in a number of organizations and it's something we actively do in addition to running our own makerspaces as well. That's it in a nutshell.

Dale: Isn't it typical though that that grant money comes to buy equipment and not to really develop the staff needed to use the makerspace effectively?

Jon: It's not a surprise. That's what happened to us but because of the size of our institution, I was able to come on and help, and we had two years to figure it out, to test and iterate. Not every institution will have that. So we've packaged something together that we can help people get going.

We're going to give you the equipment. We're going to give you the training, and you can be successful from the start. You don't need to take two years. Then I'll pass the torch back over to you.

A 2-1/2 Year Pause in Professional Development

That was how we worked up until March 13th, 2020, a very unique day. We had a wide range of professional development relationships. A lot of it was in western Pennsylvania — very rust belt, hands-on, manufacturing. A lot of schools either have or were on board with getting makerspaces.

We haven't had to struggle a lot with convincing admin or staff that a makerspace is a cool space to have in your school. So we offered a lot of PD workshops with whatever 3D printing, laser cutting equipment, some consulting here or there. Then they were started tapering off because we had “taught them how to fish.” They were utilizing the makerspaces as best they could, mainly at the middle and high school levels.

Then the pandemic hit. Professional development went out the window. Nobody had the time or the effort the last two and a half years to do anything.

Now, suddenly around January of this year, everything seems to have clicked back on. People want our programming again. PD is starting to be asked for, but it's a different style of PD. Staff turnover at schools, even schools local to us that have makerspaces, has been tremendous.

Creating a Mission for the Makerspace

People are finding they have makerspaces and they don't know what to do with them. So we crafted a professional development that we've run a number of times. We piloted it at ASTC conference that we hosted last fall and then with a couple of schools in the area. We call the professional development "making a meaningful makerspace."

We work with schools that have found a makerspace — they have equipment there and they don't know what to do with it, or they have some funding and they want to get on board with this. They don't know where to start. So we come in and we don't even lead off the discussion with technology such as here are the 3D printers you need, here's the brands, here's the laser. We don't do that.

We work with them for hours to bring in stakeholders. It's students; bring them in to our session; have your eighth graders come in here with the teachers, with admin, with some parents, and we're all going to work together to find out why you want this space.

People get the grant and they throw $80,000 of 3D printers into a room, and then they just sit. They don't know what to do with them, but we work with them. Why are you opening this communal space? What do you want to do with it? We teach technological literacy and fluency; we make makers. But what do you, this individual school, what do you want to do here? Let's get voices from all over.

We walk them through a process of beginning a mission statement. Then we let that drive the conversation of what equipment is best going to serve this mission, and then how can you grow from there?

Dale: That's an interesting point of view because what I've found also is that makerspaces that didn't get the money and that grew organically tend to solve those things naturally. In order to get the money right. Yeah.

Jon: That's the right way.

Dale: Give me an idea how long is a professional development?

Jon: That specific professional development that I just mentioned, that one we generally can run in a day, about five hours. But we can divide that up. We have found that in five to six hours, we can walk a group of people through the process of examining their assets, examining what it is they want to do, helping prompt and get them to try to codify down that idea into a few sentences and then begin the process of exploring the tech. So, we'll bring the tech with us, but we just push it off to the side in the room because all of our equipment is modular and mobile.

We spend most of the day getting them to think about what it is they want to do. Then at the end then the big reveal, we turn on the lasers, let's explore. So that's like a synopsis style day of just what do you want to do? Here's the cool tech. But then of course we consult. We're very flexible, just as you would expect in that if a school calls us and says, Hey, we have a laser cutter and a 3D printer, we have a general idea about what we want to do with these.

We can generally get people to competence on a 3D printer and a laser cutter workflow in three hours. So we're very flexible and all over the place. We don't have a spreadsheet that says, this will take this amount of time. You really listen to what it is they need, come up with an idea and then work out the charges at a later date.

Examples of Schools

Dale: Can you give me some examples of schools that you have worked with?

Jon: I'll give you a clear example of a local school here that we have partnered with for years, and it is still envisioning the makerspace as that computer room of old or like the drop space, You have all of your curriculum and then now let's just add making.

And we're like no. I mean, that's better than nothing. Yes, get your space. That's probably some of my background and also the science center itself is we don't attract just STEM professionals. I come from a language arts background. I think I read your biography probably years ago that I think you had a language arts background as well.

Dale: Yes. I do

Jon: I remember that and we all have such a unique skill set here, but we have a lot of people that are in humanities here, but are also informally learning STEM and tech and design. So what we have come to with our space is to show schools and other organizations that the skills that are learned in this space are applicable easily to STEM. That's easy. You know how you can teach science, tech, engineering and math in this space. The cooler part is that a student who learns how to 3D print and fail and do it again and again, and then work with their peers on a project, they can take that same skill set to a language class. How do you write a paper? It's the exact same thing.

Dale: Iteration.

Jon: Iteration. So we really want when we're working with these schools, that this space is not perceived as a drop zone. It's not perceived as just getting a maker grade. This is a way that you can teach the skills that you're trying to teach them.

That's exactly what we've done with Schiller. It's Schiller STEAM Academy, that's located right here. We've had a five-year partnership with them that they had one 3D printer in their room and we had some grant funding. We came into their school for a couple of weeks and they got hooked.

Then we worked with them to help procure some more equipment. We did some of our traditional PDs with them, and again, I'm talking years that this was going on to the point now where Schiller has a full-on makerspace, a teacher that is in charge of that space, and then also all areas of their curriculum-- so language arts and history make use of that space. Students are learning skills. So we really have shown them that it's not just science kids that are going to be using this. It's really applicable across the board.

And then same with another example in a non-school lab that we helped install, located about an hour and a half north here of Pittsburgh. It's called Valley Fab Lab. They started with, “Hey, we have X amount of dollars. What equipment should we buy?” They went ahead and bought all the equipment and installed it in this space. The pandemic hit. So it wasn't a great time for them to try it.

Then they came back to us after things had eased up in 21 and 22, and we came back and really helped them examine their community. What are the needs of your community? We helped them derive a mission statement, and they're now doing work not just with science, tech, engineering, and math, but they have opened up space for business incubation. They have opened up space for students to come and do homework after the fact. So again, that's just two instances of work that we have done where we really want to broaden out. It's not just STEM that's occurring inside of here.

Masterful Mistakes

Dale: What I'd call traditional education is subject-based. And what you're talking about is process-based learning, right? Learning's a process. You can get better at that process and you can apply that process to anything, any subject, But it tends towards this active learning model of how do I do something? Not just “oh, I'm absorbing something,” but how do I know how to do something? Whether that's art or science. It's all about the process really. How do I do science? How do I do art? You have to have a process for doing those things, right?

Jon: So anecdotally what I've noticed, having been a classroom teacher who was teaching to tests, is this is “choose your own adventure” at our museums; we'll help guide you.

Our makerspace, or when we take our makerspace out to schools, operates often like a traditional classroom. There's an instructor, where we have knowledge and we're helping. What I noticed is the fear of failure or the fear of mistakes is far less prevalent in our makerspace. In fact, we actively encourage it in our lab.

We have a wall called Masterful Mistakes. When a student does a really cool project that works great, we don't keep it. We keep the spaghetti noodle mess; we keep the birchwood that caught on fire. We keep the box that was all misaligned. We put it up on a shelf. We have a wall full of these mistakes.

So we set the precedent in our instruction that you are going to make mistakes. That is the point, and you're going to get better in what I hope that a student will take out of that space. Or if a school opens up a makerspace and they are trained with us and they take on that philosophy, that if a student's going to go in there and learn like it's okay, like I don't need to get this perfect.

And then they can apply that to the rest of their learning. So it's a very different style. As you mentioned, it's about the process. We're teaching you're not going to get this right the first time but let's have some cool tools that you can experiment with.

Dale: I think what making is taking some idea you have in your head and trying to realize it and bring it to life. And that idea changes as you make it real. Or you think about how it could be better. When you show it to someone else, they now participate in that idea and they say, “oh, have you thought about this?”

So it's a very satisfying process and I guess that's what I'm ultimately advocating for, how kids really can benefit so much from approaching learning as a process, something they do, and how making, creating, solving problems — all these other things are processes that apply to lots of different things.

Jon: Absolutely. I concur.

Dale: Our country has been doing No Child Left Behind for 25 years or so, right? There really has been no new initiative from the federal government or even state levels to really move past NCLB to something new. Our science centers and other places have held on to this hands-on learning model, and kept it alive in informal learning in conjunction with the maker movement. It looks to me like they're the ones with the new ideas about where education should go, if people are looking for new ideas. Kids aren't motivated, they're not engaged. Science centers have been a bit of an incubator for what I think is next in education.

Jon: It's weird— the words you're using are very apt. I was having a few conversations earlier today with our development team. We were working on some grants and I came to the realization that even within the Carnegie Science Center, I and my co-director Tina, we oversee our STEM education department which encompasses the Fab Lab and another of other departments. We're the incubators within the museum.

It's like we get the creative freedom to test out something like a Fab Lab and find out how it's working in this setting. And I also agree with you too, that over the past about four months, I personally have been pulled into five different meetings, one of them involving Pittsburgh public schools and the superintendent who is pooling cultural institutions together and basically saying help.

What are we doing and how can we work together to do this? I'm really seeing a segue out of just us being seen as a field trip destination or a place to take your kids on the weekend, but us having something that we can bring to supplement the education that is going on right now. Students are having some gaps. The trend I'm seeing over the next year or so is that two-year gap the students had when they were learning at home on their screens means that a makerspace or a fab lab such as ours is extremely important for their socio-emotional learning. We want to be bringing students together with adults and having them learn how to make eye contact, how to work together, how to do these things that they didn't have an opportunity to do.

So I agree that we're in a unique spot at the moment.

Dale: It's asserting that learning is a social experience and students benefits from being in a group of people doing this together, as opposed to being alone. Being together, we can learn a lot from each other. Especially creatively.

Jon: Agreed.

Dale: Jonathan, thank you for your time. I really appreciate it.

Jon: I'm always happy to touch base.