Maker Clubs, Classes and Hubs

Which one is right for you and your school?

Happy New Year to you!

Given that a school has decided to create a makerspace, a question I have heard asked is: “Should I start a maker club or a class?”

Of course, the best answer is “both” but let’s look at what a club offers that a class doesn’t and what a class offers that a club doesn’t.

A maker club organized by and for students typically outside of the school day offers the following positives:

A great way to build a core group of makers who use the makerspace regularly, pitch in to help keep the place tidy and also help greet and on-board other students.

It offers a sense of belonging like playing on a sports team.

It opens the makerspace to students for the use the workshop and its equipment for their own projects, work that they choose to do. It gives students the opportunity to explore their own interests on their own time.

There is not a tight time limitation on how much they use the makerspace.

There’s no grading. The bar is lower for just trying things out.

There are some negatives to a club, which mostly translate into the positive reasons for doing a class.

Students get school credit for the skills they are developing and the projects that they build. It shows that the school values the work the students are doing. Making is a good way to learn in school.

Some students don’t have time outside school to participate in a club. Others might not choose a club but would be motivated to take a class.

Some students benefit from the structure and incentives provided by a formal class.

Many of the maker classes are electives. It may require recruiting students into the class. I know of some private high schools have maker classes that are required for all students, which does guarantee exposure to those who might not choose it.

Making can be applied to teaching existing curriculum by introducing hands-on experiences that help engage students across many types of classes.

The biggest challenge in some classes is that students are externally directed to do projects, based on the curriculum or the teacher’s goals, but then they don’t have the opportunity to develop projects based on their own interests and ideas. It can make a big difference in motivation for students to choose their own project and it also helps them develop confidence. The best maker educators figure out a way to balance the needs of the curriculum and the interests of the students.

Clubs and classes generally are usually managed by a single teacher. The two can actually work together quite well. Students in the club can be peer teachers in class and help other students become productive. This can also take some of the load off of the teacher. The class can help develop interest among students in joining the club.

Clubs and classes might lead to a third kind of use of the makerspace, as a hub. The key to a hub is not necessarily centralizing maker education but rather distributing the resources and expertise throughout the school. The hub can take the lead in training students as well as teachers so that the capabilities of the school grow and hands-on learning is seen as well-supported practice.

A hub can be used by students in class or out of class. It becomes an independent entity like a school library (and sometime might be co-located with the library.) Teachers can devise projects in any class that students might develop use the hub as a facility. A hub can also organize fun group projects that offer the opportunity for students to work together to solve a problem or building something new.

The hub model is about broadly expanding the expertise required to make use of the makerspace throughout the school. There are plenty of examples where a single teacher developed a makerspace and then that teacher left the school and the makerspace goes unused. The investment in time and equipment is lost because the expertise and vision are gone. A hub is a cooperative effort.

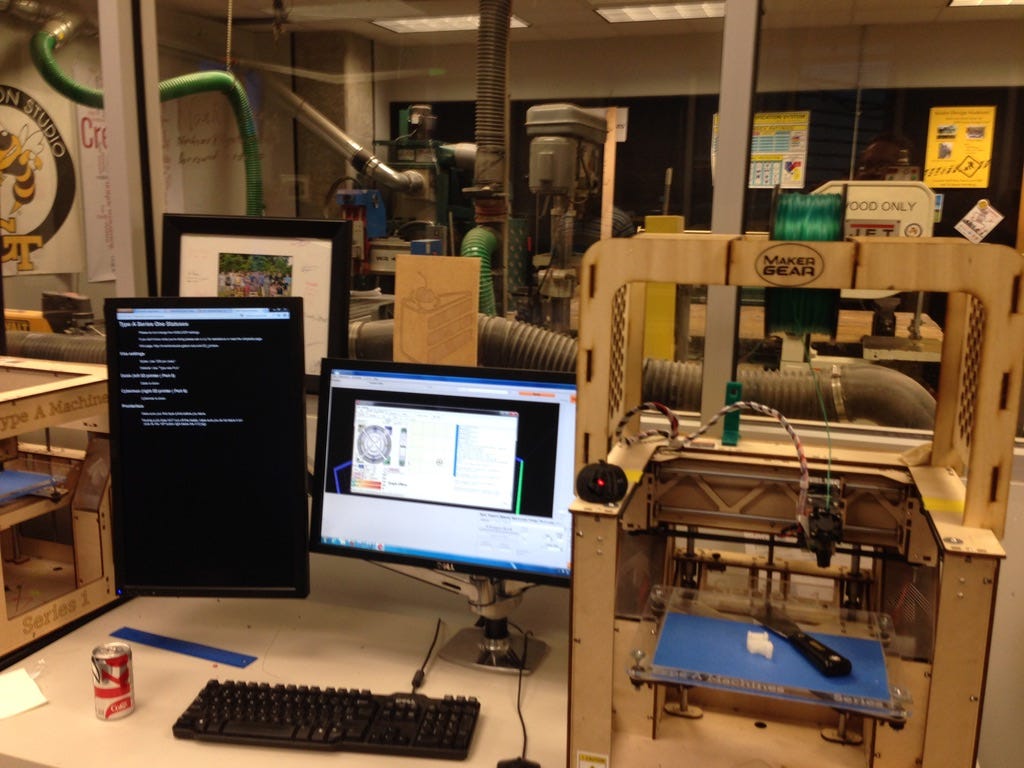

One early example of a hub was Georgia Tech’s Invention Studio in the Mechanical Engineering department. Now it’s called the Flowers Invention Studio but the mission then and now is the same: “We support ALL students, staff, and faculty in building their dream project, whether it’s for research, personal or academic usage. Our tools are 100% free to use.” It’s such an amazing benefit to the community.

On a visit in 2013, I watched a member of the school’s janitorial service working on his own project, which required using the waterjet. He was excited to be able to do the work, and it didn’t matter that he was a staff member, not a student or faculty member. Opening up to a community of users can be surprising, seeing what kinds of projects people want to do on their initiative, the projects they dream of — it’s key to understanding the maker movement.

At the Invention Studio, there was a student club that had responsibilities for managing the makerspace, including greeting new students and making them feel welcome. The Invention Studio also had paid staff and a comfortable budget.

Dr. Craig Forrest, who started the Invention Studio told me that once the place existed that professors began assigning projects to students that they could do in the makerspace. Without the space, they wouldn’t have assigned hands-on projects. When you create the capability, it gets used, even in unexpected ways. He told me that “these facilities, infrastructure, and cultural transformation are demonstrating the value and sustainability of hands-on design/build to stimulate innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship in engineering undergraduates.” (See this Makezine article about the Georgia Tech Invention Studio.)

Maker hubs are more than a makerspace, more than a club or a class. They can be a catalyst for cultural and institutional transformation that bring out the best in students and teachers. They can increase the flow of new ideas and new skills coming from the community and going back out to the community.