Hearing "Hands-on Experience"

It's not just AI that needs to learn more from interacting with the world

President Biden’s State of the Union address last week caught my attention. During a speech when various people in attendance stand and applaud as the President says something they like, I wanted to stand and applaud when I heard him say “hands-on experience.” He mentioned it in the following context:

I want to expand high-quality tutoring and summer learning time and see to it that every child learns to read by third grade.

I’m also connecting businesses and high schools so students get hands-on experience and a path to a good-paying job whether or not they go to college.

In a speech with many such aspirational goals, the question is will “summer learning”, “learning to read”, and “hands-on experience” become a priority for this administration and lead to concrete actions? Otherwise, it’s the same kind of thing politicians say because it sounds good but it doesn’t really mean they are committed to doing something.

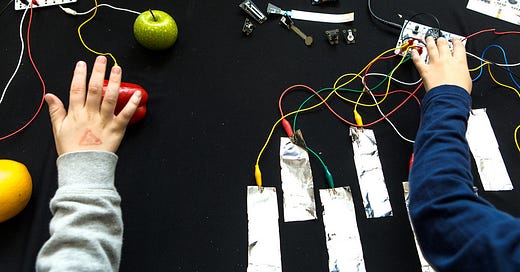

Summer learning for students should be about having rich experiences, the kind of activities and projects we have promoted as part of Maker Camp. Summer learning shouldn’t be feel like or look like school. Students should have the experience of learning from interacting with the world around us, which includes learning from their peers. It should be fun and playful.

High schools should be more fun and playful, too. They should offer more hands-on learning experiences because that’s how kids learn best. Yet it is not how most children are taught. What we mean by maker education — is to think less about what students are taught, and more about what students get to do and the process of doing it.

I wish more people in D.C. would make the connection between “hands-on learning” in school and the kind of jobs that can be filled by people who have the “know-how” to do things.

Embodied Cognition

In Axios/Science report, Alison Snyder writes that AI researchers think that “‘embodied cognition’ is a necessary ingredient to achieve advanced AI.”

A fundamental facet of intelligence found across the entire animal kingdom is beginning to be unraveled using AI, neuroimaging and other tools.

Why it matters: Language, reasoning and other abstract skills tend to get the most credit for human intelligence. But gaining knowledge of how the world works by walking, crawling, swimming or flying through it is an important building block of all animal intelligence.

The story adds: “Embodied cognition also helps animals understand how the world works — by experiencing it. ‘There's an argument to be made that biological systems learn from interacting with the world," says Jochen Triesch of the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies.’”

I’ve thought that “embodied cognition” is a more intellectual-sounding term for “hands-on learning.” Interesting, isn’t it, that such a common-sense notion that “we learn from interacting with the world” is what AI needs to get beyond digesting and regurgitating large amounts of data?

Perhaps educational leaders should consider learning from AI and realizing that students are wired to learn by experience, by interacting with the world? It’s how their biological system works.

Where talent is coming from?

The same Axios article provides data from 2021 on the percentages of the U.S. STEM workforce that are born outside the United States. The higher the degree level, then the higher the percentage of foreign-born workers.

While it is great that the U.S. can attract top talent from around the world, and that such talent wants to come here, it is not good that STEM industries have to depend on them. The opportunity is for the U.S. to develop more of its own talent and get them into well-paying jobs — it’s real but unrealized.

There were 36.8 million people in STEM occupations in the U.S. in 2021 — about 24% of the country's workforce. That's about a 2% increase since 2011, according to the congressionally mandated report.

Foreign-born workers accounted for 19% of all U.S. STEM workers and 43% of scientists and engineers with doctorate degrees in 2021, the latest year of data in the report.

About 58% of doctorate-level computer and mathematical scientists in the country's workforce — who drive the development of artificial intelligence, computing and other technologies deemed critical by the U.S. government — were born outside the U.S., according to the report.

If U.S. business finds that it can acquire talent from overseas easily and cheaply, it doesn’t have to concern itself with the quality of the U.S education system or how deep the talent pool is in the U.S. It can skim the cream from the top in this country and any other country. That might be good for business but it leaves too many of our own people behind.