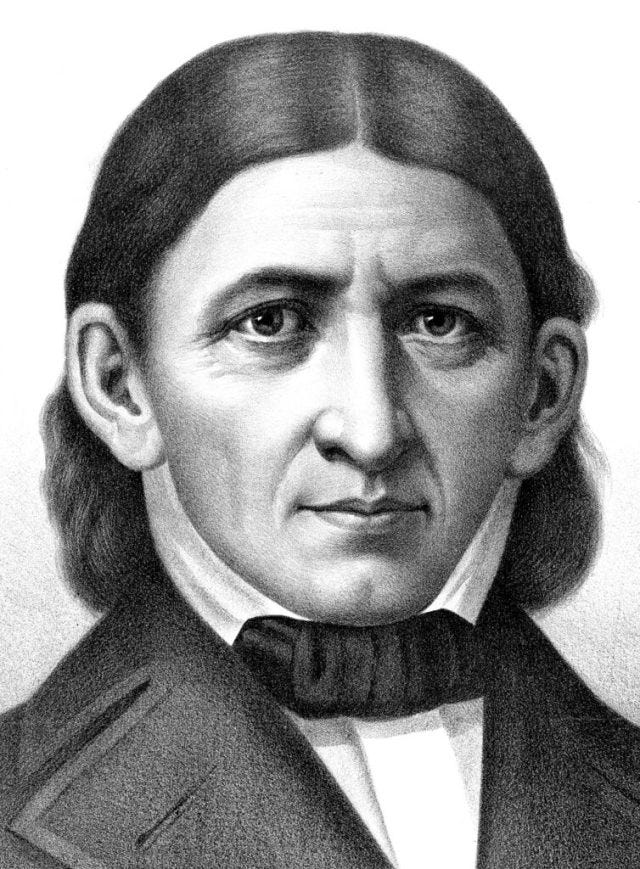

Celebrating Friedrich Froebel's Birthday

His mark on modern art and engineering was profound; his innovative ideas for kindergarten are largely ignored today

by Doug Stowe

April 21, 1782

If Friedrich Froebel were alive today he’d celebrate his 242nd birthday this month. I doubt he would be celebrating what’s happened to Kindergarten since he came up with the original idea.

In about 1840 he and fellow educators were walking over the crest of a mountain pass, and he proclaimed to the others, “Eureka! I know what to call my youngest child! Kindergarten!!” These days, few remember the origins of Kindergarten or know that it was invented by someone, let alone remember the original philosophy behind it. With so many having proclaimed Kindergarten to be the new first grade with ever increasing emphasis on reading and ignoring the child development that Froebel had in mind, Froebel would have rolled over in his grave several times by now. His “youngest child” might not be recognized by him.

On this day I celebrate his remarkable contributions even though they’re largely ignored, even among those dedicated to education.

As a young man and a troublemaker in school, young Friedrich had been farmed out to the care of an uncle, a forester in the Thuringien Forest in Germany. There he developed an interest in nature, and a passion for carving things from wood. As a young adult he considered becoming an architect. Having abandoned that, he had greater influence on Architecture than he could ever have imagined, which I’ll mention again later.

As a young man at university, he became the assistant to Christian Wilhelm Weiss, noted crystallographer and mathematician. In working with crystals in Dr. Weiss collection, he observed that given the right conditions for growth, crystals grew from a pattern within. Building on that awareness, he realized that children were much the same… starting with a spark from within, then provided all the right nutrients and conditions for their growth, remarkable development would take place.

Inspired by his study at Leipzig University with Dr. Weiss, and perhaps by his own woodcrafts, Froebel developed a system of what he called “gifts” — sets of blocks and other developmental objects. His were some of the first educational toys developed for children and were an influence on all subsequent early childhood development tools and educators. In association with the gifts, Froebel also offered “occupations” — activities through which the children could test and put into direct action what they were learning.

Those blocks in the hands of Frank Lloyd Wright led to his career as an architect, as he noted in his biography, “I can still feel those maple blocks in my hands to this day.” The mark left by Froebel’s Kindergarten on modern art and engineering were profound. As a nearly blind kindergartner, whose remarkable intellect had not yet been observed, Buckminster Fuller began working with triangular structures using a Froebel gift, “Sticks and Peas” in which toothpicks were used to build structures connected by softened dried peas. While all the other children were busy making rectangular forms that he could not see, young Fuller found strength and stability in the ways triangles could be connected into rigid shapes. Fuller’s shapes gained the attention of his teachers. Later his inventions had the same effect on the rest of the world, making me wonder whether advances in engineering might have been delayed without Froebel’s Kindergarten.

Domes anyone?

In addition to Wright and Fuller, other artists and architects were strongly influenced by attendance in Kindergarten and play with Froebel’s gifts including Georges Braque, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and Le Corbusier.

We would do quite well to remember Friedrich Froebel when we consider the needs of American education and our kids. These days the pressure is on for reading in Kindergarten. Froebel had other things in mind. Froebel saw the purpose of education as being the discovery of our interconnectedness within the frameworks of family, community, human culture and nature. So, if you want to know why in early day Kindergartens, they planted gardens, took care of small animals, and did real things, it was Froebel’s grasping that spark of order and potential growth in crystals, in nature and in each child that led the way toward their becoming adults integrated with society and able to fulfill the needs around them.

In 2008 I attended an educational conference at the University of Helsinki, and as I grew tired of lectures, I found my way to the university wood shop where Kindergarten teachers were working on their master’s degrees—learning to teach woodworking to kids. While Patrik Scheinen, Dean of the Faculty of Behavioral Sciences at the University of Helsinki, was unable to offer direct evidence connecting their approach to Kindergarten with Finland’s success in the international PISA testing, one cannot help but wonder. While placing less direct emphasis on reading and more emphasis on doing real things, Finland has ranked consistently at the top in reading, science and math.

“To learn a thing in life and through doing is much more developing, cultivating and strengthening than to learn it merely through the verbal communication of ideas.” — Froebel

After Kindergarten was first introduced in the US, many educators noting its wondrous effects, proposed that other grades should become more like kindergarten.

In the early 1860’s a Lutheran Priest in Finland was chosen by the Russian Tsar (who at that time ruled Finland) to develop a system of folk schools. Uno Cygnaeus travelled over much of Europe to review various school systems in different countries, and he was most impressed by Froebel’s Kindergarten. A problem was that Kindergarten was aimed for children ages 3-8, and Cygnaeus needed to extend it up into the upper grades and he did it through an added system of craft education.

Cygnaeus use of crafts was based on a Froebel concept, “Self-activity” which recognized that “To learn a thing in life and through doing is much more developing, cultivating and strengthening than to learn it merely through the verbal communication of ideas.”

Cygnaeus idea was to extend self-activity through engagement in crafts making real things in service to family and community, not as a program for vocational training but as a means of human development, creating skills of both hand and mind. Craft education, deriving its name from the Swedish word slöjd meaning skilled or handy, became an international movement called Sloyd that played a large role in the development and diffusion of manual arts training in the US and around the world.

Educational Sloyd had a simple philosophical foundation. Start with the interests of the child, move from the known to the unknown, from the easy to more difficult, from the simple to the complex and from the concrete to the abstract, thus building skills of mind and hand by doing real things.

Following that simple formula, coupled with Froebel’s goal of helping the children to discover their interconnectedness with all things, offered a revolution in education that inspired John Dewey, Herbert Spencer, William James, and a whole slug of additional educational theorists, up to this day, but who are still largely ignored by the powers that shape American education.

It's widely recognized these days that American education is a mess with student apathy and absenteeism, and trained teachers leaving the field of education faster than warm bodies can be brought in to replace them. Kindergarten was best known for learning through play. Restoring a sense of play would serve students, teachers, and schools well and fix most of the problems facing American education. I’m the son of a Kindergarten teacher who received her training long before the origins and purpose of Kindergarten were forgotten. When she would meet parents for school conferences, she would advise that when they asked their children what they did in school that day, and they answered “play,” that was the right answer, for in play learning is at its best. And for all concerned, teachers too.

I retired from teaching woodworking to kids at the Clear Spring School in northwest Arkansas in 2023. I continue to teach adults, whom I’ve discovered learn the same way as kids, best when hands on. I’m the author of 15 books and over 100 articles in woodworking magazines and educational journals. My book, Making Classic Toys that Teach offers instructions for making Froebel’s gifts. My book, Wisdom of Our Hands: Crafting, A Life explores the necessity of hands-on learning.

Doug wrote an article for Make: Ginormous Froebel Blocks

Doug also shared this excerpt from a documentary on Froebel, “History of Kindergarten Froebel to Today,” that features him and some of his students.

Find our more about Doug and his books at dougstowe.com.

Froebel’s gravesite is marked by the sphere, on the cylinder, on a cube, but all done in granite.