Authentic Learning and Making in K-12

A conversation with Michael Stone of the Public Education Foundation which has created 34 Fab Labs in K-12 schools in Hamilton County, Tennessee

Michael Stone is an educator who led efforts to create 34 Fab Labs in K-12 schools in Hamilton County, Tennessee, despite not thinking of himself as having any skills or interest in making. He was a basketball coach with a degree in computer science. Now, as Vice President of Innovative Learning for the Public Education Foundation. a nonprofit in southeast Tennessee, he's an educational leader who has embraced maker education to help students develop technical skills but also to learn about creative problem solving and collaboration. He talks about making as authentic learning, involving real problems and solutions, and which leads to authentic assessment.

This is an episode of the Make:cast podcast. You can listen to the podcast, watch the video here or on the MakerEd Channel on YouTube or read the transcript below.

Michael: When kids are engaged in that process of taking an authentic problem, being tasked with building a functional solution and packaging their learning in it, and then getting tons of feedback on those essential skills as they build their solutions out, we've started seeing students are developing a sense of identity. They're starting to discover like what do they like to do, what kinds of problems they like to solve, and what are they good at? When they have that sort of, that trifecta, the intersection of those three really empowers them to make informed decisions about their future.

Dale: Welcome to Make:cast. I'm Dale Dougherty.

My guest today is educator Michael Stone from Hamilton County, Tennessee, where the city of Chattanooga is located. Stone is responsible for developing Fab Labs in K-12 schools in Hamilton county. There are 34 of them to date and the number continues to grow.

In this conversation, Michael talks about the reasons why they're creating Fab Labs and it involves a big shift in education towards what might be called authentic learning, and authentic assessment.

It is what school should be for more and more students and Hamilton County shows that it can be done for larger numbers of students in public schools today.

Michael, let me just ask you to introduce yourself and tell us about who you are, where you are.

Michael's Background

Michael: Sure. I'm Michael Stone. I'm the Vice President of Innovative Learning for the Public Education Foundation. We're a local nonprofit in southeast Tennessee.

Dale: What are you known for?

Michael: We do a lot of professional development for teachers and principals and I think probably why we're connecting today. Part of that PD, a lot of that professional development last seven or eight years is focused around how to integrate Fab Labs in schools.

We've been working with Volkswagen Group of America and the State of Tennessee to open what is now considered the largest network of school-based FabLabs. We have 34 FabLabs in schools. We call them Volkswagen eLabs, and that will be opening another nine this summer. So we'll have 43 in K-12 public schools in our community by this time next year.

Dale: 43. That's amazing. How did this start? How did you get involved in this?

Michael: The abridged version. I was a classroom teacher. I taught math and computer science at the high school level. In full transparency, I got into teaching because I wanted to coach basketball. I'm 6'9" and here, you can't coach boys basketball if you're not a teacher.

So I got my degree, became a teacher. Turned out I loved it. I loved teaching at least as much as I loved coaching. Nine years into my career had an opportunity to make a change. Went over to a local STEM school and they were looking for someone to open a Fab Lab. I didn't know what a Fab Lab was.

I had almost no, like technical or mechanical skills. I told the principal in my interview, I didn't own a power tool and I paid people to change my oil. I didn't identify as a maker at all. I did have an undergraduate degree in computer science. So the digital side I was pretty familiar with.

But I was enamored with what the school was doing to change how they were engaging kids in learning. They were all about having kids take ideas from their head and bring them to reality through some sort of specific process.

Dale: That's what I think a maker is. That's all it is --taking an idea and bringing into reality through some process.

Stumbling into Fab Labs

Michael: So like we stumbled into FabLabs, the Fab Foundation, out of MIT and we were like, okay, what if you rethought how you did school and if kids just happened to have access to a Fab Lab? What would you do different in school? What I was excited about was the principal said-- his name is Dr. Tony Donan-- he said, "I know what we won't do is we won't spend all day teaching kids lecture style or, didactically how to use 3D printers and laser cutters and the tools. We are about putting kids into the most authentic situations as possible and packing rich learning into those situations."

I jumped off the cliff. I stopped coaching, jumped in and went there. That was 2014. Two years later I was with the foundation and Volkswagen made a significant investment to start expanding that model that we were building into other schools.

And here we are today, 34 labs. We're working with teachers all over the region and now over the country. We've supported another two dozen or so labs in different parts of the country to open up in schools. And really it is about helping schools reimagine what's possible. How do we really train kids for the future? A piece of that we think, and I'm sure we'll get into this, but a piece of that is, they have to develop the ability to quickly learn new technical skills and apply them in a given context.

And another piece of that is based on, we based a lot of our model off of the work, out of out of Harvard. Years ago, Tony Wagner talked about survival skills. Like a lot of like critical thinking, creative problem solving, productive collaboration, like so much of school doesn't give kids the opportunity to develop their creative muscle or to truly collaborate or engage in project management.

So FabLabs became a modality for us to say, what if we change how kids engage in traditional learning by really preparing them for a world where the content I know may be the least valuable asset I bring to workforce. My ability to learn new content and my ability to apply what I've learned those skills and competencies in a new context is ubiquitous. It's transferrable and it's personal, right? It's based on my interest. We've leaned a lot in that direction. It's been a wild ride.

From Master Teacher to Master Learner

Dale: So talk a little bit like the very first one. Yeah. What was the challenge of the very first one?

Michael: Me. I was the challenge.

Dale: That's honest. That's very good.

Michael: It's also true. So I, like I said, I told the principal like, I don't have these skills. He changed my life with his response to that observation. I was basically pulling my name out of the hat for the job. And he looked across very somber and he said, honestly, I don't care that you don't know what a CNC router is. My only question is, are you willing to learn it? And would you learn how to do that in front of kids? Would you be willing to learn it with kids beside you?

I was like that's a question a principal has never asked, but if you'll let me, I'm happy to do that. I believe that just about anybody can learn just about anything. You just have to give 'them time, space, and support. If you'll do that, I'll be happy to do that. He said "look, we want our kids to see their teachers not as content experts or what the traditional sort of sense of master teacher, we want them to see"-- he used the term "master learner." "We want them to see a master learner in front of them, someone who can learn anything."

Dale: That's powerful. That's powerful,. It's the shift we're talking about here. That's a big one, but it doesn't diminish the role of that person. In fact, it makes it more important that teacher is a master learner.

Michael: That for me was the paradigm shift was really the hard part. It turns out the technical stuff, there's a wealth of information at our fingertips. Learning the technical stuff is a matter of fortitude, effort and access. I was willing to get after it and learn. That was fine. And we found, it turns out, lots of teachers are willing to get after it and learn the technical stuff.

The bigger hurdle was the paradigm shift for me. I had taught calculus. I made the argument that like it took mathematicians 2000 years to go from algebra to calculus. I can't ask really interesting questions and my kids suddenly make that leap on their own. They need an expert to teach calculus. To some degree, I still believe that. What he helped me see was students actually need, even in that calculus setting or that hyper technical granular content setting, kids don't actually need me to teach them calculus. They need access and resiliency and opportunity, but the world's best calculus teachers are available online. Why would I aspire to usurp them? Why wouldn't I give my kids access to them and support them in that process? Whether that's calculus or 3D modeling, doesn't matter.

Coaching

Dale: Just to drill down for a minute, because you said you got into teaching as a coach, and I've often thought that coaching actually is a better model of what we're talking about here than teaching. You're looking at getting the students to perform, not yourself. Yeah. And that a couple of things, one is practice seems to matter in everything. So the more you do it, the better you do it. Having a coach who helps guide practice and gives you feedback is really important.

Like you can do a lot on your own, but when someone watches you and gives you feedback on that process, you could be better at that process. Your performance turns out better, right?

Michael: Oh, absolutely. There's a reason why I don't know who the best golfer in the world is today, but Tiger Woods heyday, there's a reason he paid his coach a million dollars a year. It wasn't because the coach was better than him at golf. He was the best player in the world. Right? But outside perspective to see where the opportunities for improvement. That matters.

Dale: I think for a lot of teachers that don't know the technical stuff, if they saw themselves as coaching kids in a process. As a teacher, you're an aware human of how kids behave, what do you see? What do you do about that? Their problems typically aren't technical, they're more mental. I'm frustrated or I don't understand something.

Michael: Absolutely.

Dale: You try to come up with strategies to try to help them, but help themselves largely. In many ways we need kind of maker coaches and such .

Michael: Yeah.

Dale: In soccer, the young kids are playing, it's the parents that are coaching them. They probably never played the game themselves. You care about them and you're going to get them together at that level. On the other hand, as the kids progress, they get older, they get better coaching usually if they want to play the sport. The same should really be true in school. By the time they're out of middle school into high school, the teachers, coaches should be able to introduce more complex problems to them and more complex tools to solve those problems.

Michael: I think this is something that the Make organization and sort of the maker community has really done extraordinarily well. Is that exactly, right? You have helped makers document processes and be a part of a community. Like where does that help come from? Where does that coaching come from? Increasingly in the maker community, it comes from the community. I think in schools thinking about approaching education for much more of that mindset, that paradigm has profound, potentially profound impact. In the sports analogies or the coaching has any other element that's really valuable is we never approached coaching-- I didn't run basketball practice, and the culminating event was always more practice or some trivial performance, right? We actually like built the product and we had a game when we could see, did the practice pay off? As we bring FabLabs and embrace maker education and really think through the lens of like, how do these rich and authentic experiences change how we develop a sense of like deeper learning?

There's all kinds of robust impact for the student, for the individual student and education as a whole. We get to have that authentic piece right? When there's authentic experiences, the teacher no longer has to, I don't want to say waste time, but waste time, motivating kids because they're intrinsically motivated. I have agency. It's my idea. You don't have to coach me on that.

Dale: That's what I was excited about. When I started, I didn't really know if this appealed to kids, but through Maker Faire I could see that it did. You didn't have to twist their arm. They wanted to do it. Now the question is, it's like a kid that wants to play sports. One of your job as a coach is, is not to ruin their love of that sport. The intrinsic motivation they had to play. They enjoy that, but if you're beating them up all the time, they shake their head and feel defeated and stop enjoying it.

Michael: That's right.

Dale: Part of that is keeping them really engaged in doing that. You talked, we don't necessarily have the competitive end goal always here. I always felt like what is our Maker Faire component of exhibition, of sharing your work publicly to people that don't know you, don't know what they do, is thrilling. Also challenging. But very motivating. If people say, that's really cool, you I like what you did.

Authentic Assessment

Michael: I think the competition in sports so often, like a school level or sort of higher level, it's an authentic assessment of your skill level. It's an authentic assessment of how you've developed both individually and as a team if it's a team sport. In this context Maker Faire, public exhibition, public displays, engaging in a community, even just bringing my idea to fruition, right? There's all kinds of authentic assessments that's happening, right?

I'm getting to see, did my idea work? Was I able to build the thing I thought was possible to build? Could I bring this thing to reality? To me, it's way less about the competitive element. Is my thing better or prettier, fancier, right? There's so much self-discovery and intuitive learning that happens instinctively, organically in that process of going from idea to conception that you really have these are life-changing moments that happen regularly that are unpredictable, right? Tapping into that dynamism, I think is really powerful. It's something we miss in a lot of the traditional scope of public education. Just education in general.

Dale: One of the real things that we've been arguing for is that this is available to every kid. Like it isn't just some select group that have a unique makeup but that this is really accessible. It hasn't been physically accessible -- the tools and things haven't been available to them, but that's why this is so important.

You're creating networks of FabLabs and making it available to more and more kids. You could have kids self-select in and you have a little club of kids doing this, but the challenge is really to get more kids exposed, even ones that don't understand what it is initially.

Michael: In our local context, I could speak to, I don't want to suggest this as a silver bullet, but I think we've made some interesting progress in that regard. And you're right. Step one is we've been blessed to have Volkswagen as a local partner and providing financial support to be able to just physically expand access. While we don't have a hyper focus on the technical skills, the kinds of tools that are in a Fab Lab, the rapid prototyping tools, the digital fabrication tools, they allow students as early as five and six years old to really produce like viable market-ready real solutions to real problems.

We talk a lot about authentic solutions to real problems. That's a powerful piece. So having, just having access matters, but there's a lot of places that have tools that aren't really rethinking the implications for education when you have them and how do you expand access? For us, that has come back to the fundamental question of like, why did we start with FabLabs to begin with, which really looked at that work from Wagner of how do we equip kids to develop those essential skills.

We tell the story pretty often, but if you imagine walking to any, let's say high school in the country and ask the school. Hey do kids get better at math at your school? Basically, everyone in the building, not just the math department, but everyone in the building could tell you what the structured plan is to grow students mathematical prowess through high school. There's probably state standards that are scaffolded. We could ask the same question about science or history or English, but if we ask that question about something that we've never heard anyone balk at, like collaboration, does collaboration matter? Every educator in the country is yes.

But if we say like, how do kids get better at collaboration in your school? It's either like crickets chirping or they'll respond to something like we do a lot of group projects and that's like saying we do a lot of math. I mean like our kids get better at math. So what we've done is we took essential skills, like collaboration.

We said, okay, what if we focused on collaboration through the lens of personality diversity in freshman year? I'm competitive. You're sensitive. How do we work together? This is the world we're about to enter. We need to be prepared for this. And then what if that looked like pure accountability sophomore year and looked like building a professional network junior year. All of these different layers of collaboration.

Dale: I'd love to see more on that because I think one of the challenges in maker education has been defining progressions through the years. Okay, we have a space. They just have more access to it the older they get, but what are your goals in and challenges for them? How do you expect them, just as a ninth grade basketball player is not the same as the 12th grade player.

Michael: For us, leaning into those essential skills, so that's actually what we assess. We provide feedback now on the sophistication of the product or the technical progression for the students. We've actually just built an app that helps schools do that.

Dale: Yeah. Nice.

Michael: We're just piloting locally, which is really interesting. But even in the app, we track simultaneously technical skill progression, which is the content of a Fab Lab, right? And then we track the essential skill progression. We wanted to really think about what would school look like if content wasn't king and everything else was way down the list. But what if we said, what if process or essential skills were key and content matters. I taught math. I've got four daughters. I want them to learn their multiplication facts and how to factor. Without content, we limit our future possibilities, right? Without technical skills, we limit our future. But without those essential skills, we could be a technician who's a jerk that can't work with anyone. We've also limited our future.

So tapping into that, I'll tell you, we, we stumbled into a discovery that we don't have formal research around yet. We're working on it but we have a lot of anecdotal evidence. As we started working backward from high school to elementary school with this sort of model, what we realized is around grades, fifth or sixth grade, and into middle school, when kids are engaged in that process of taking an authentic problem, being tasked with building a functional solution and packaging their learning in it, and then getting tons of feedback on those essential skills as they build their solutions out, we've started seeing students are developing a sense of identity. They're starting to discover like what do they like to do, what kinds of problems they like to solve, and what are they good at? And when they have that sort of, that trifecta, the intersection of those three really empowers them to make informed decisions about their future.

If they go on to be an engineer, great. I've had some meaningful experiences all along the way that help me know maybe which branch of engineering I want to get into. If they decide to be a welder or a plumber, or a doctor or a lawyer at a non-technical position. They still have these meaningful experiences that help them understand, and they've been consistently getting feedback on how do I communicate effectively?

What does critical thinking look like? As that's happened, it's helped us recruit other teachers who may not identify as technically savvy or as makers necessarily, but when your English teachers and your history teachers are going, "I need my kids to collaborate better. I want my kids to be more creative. I need better problem solvers and communicators, collaborators." Suddenly you get faculty who previously didn't see themselves in this space, seeing the value of how the space is empowering kids to really cultivate this sense of identity and sense of self. So in a technical world, it's hyper, it's philosophical, but I think it's had a profound impact for us on expanding access because that usurps the 10 kids that opt into the robotics club.

Expanding from one school to many

Dale: Can you talk a little bit about how you went from one or two sites to was it 34? A lot of maker spaces have evolved because one or two people wanted them in a school, and then a district might say that kind of worked well in that school. Now how do we add that to the rest of the schools? They usually take that teacher out of that space and have them manage a bunch of spaces. And it's a whole other level of challenge.

Michael: It is. There's a lot there. So the quick version is we began scaling eight per year. This was the sort of outline from Volkswagen as we were partnering in 2017. Eight per year for the first few years and then just grew in that size of cohort, give or take like cohorts of five to 10 each year to just keep growing.

So that's the math on it. The how-do-you-do that is a much different question. Ton of professional development and I think the people in this matter a ton. The leaders matter a ton. So we put out, initially, the first few years, we don't do this anymore because it's grown so much, but initially we did a competitive proposal. So schools had to apply to be a part of the network to get a Fab Lab. We would provide everything; it was all funded, professional development, all the stuff and everything, but they had to want it.

Dale: That helps really.

Michael: It does because we wanted to see two things. We need the buy-in. Does the principal actually want this? Or is this a shiny toy that they think, oh, this will help me move up the ladder? But beyond that, we didn't just need to know did they want the lab? But like, why did they want it really mattered?

Were they buying into this sort of, school could be different? We could think differently about student experiences and how much were they willing to buy in. So the application process really helps schools cultivate and articulate that sort of what's their why behind this? What we looked for a lot in that then was who they identified as their teachers and specifically like what attributes did they have.

Pioneers and Settlers

Michael: What we found were, we really were looking for-- we've now gone to classify them. We went from one to nine in a 12 month span. Those first eight that we expanded to all eight of them identified teachers that we now call like pioneers. So we used "pioneer" and "settler" language. They were the ones that were like Lewis and Clark. Like just tell me there's a West and I want to go. Tell me there's something new. You don't have to hold my hand. If it's out there, I'm chasing it. It's great. So we grabbed those super early adopters, those pioneers, and gave them just enough.

Here's what we're thinking. This is the model we're trying to replicate, but we can't look the same. It's gotta be contextually relevant in your school's context. As we were doing this in inner city schools, in a rural schools, suburban, all at the same time. So they're growing and going. That next year we realize we are about 50/50 split.

We started running out of pioneers and we started getting some settlers who they needed the path carved before them. They wanted guardrails, but they didn't want to be told exactly what to do. They were willing to go build the town and settle, but they needed a path ahead of them. So we started articulating like, what are those guardrails? What are the pieces that we can provide support?

The pandemic hit shortly after that. We had a year where it was just survive mode. But we're in the South and we reopened pretty quickly, I'll say it that way, for better or worse. So we've recovered in the last couple of years.

We're seeing an interesting mix of that sort of continuing to attract settlers and pioneers, but early adopters who are willing to say, to lead the space to say, I want to jump off and try this different. I do believe the people that we've had involved, and especially the leadership that we've had involved along the way, building level leaders who saw this doesn't have to cost me test scores, right?

Our content test scores matter in K-12. It's a thing. It maybe shouldn't, but it matters, right? So can I engage kids in deeper learning and not sacrifice their academic achievement? because the moment that's off, if that's off the table, really we lose. As we started showing proof of concept, like actually when kids have many more meaningful experiences, they show up more engaged, they actually want to be at school. Like they're willing to do the math and the history and the English, because they're getting to do real work also around that. And then not thinking of the labs as a singular place, as a place where I go learn 3D printing, as a place that supports my growth and learning. I think those three things, the people, the vision, and really rethinking why we're even putting labs at schools has been really fundamental to the growth and success the network.

Dale: I just wanted to ask you in on the professional development side is that distinction you have between settlers and pioneers, whatever you call them, it's just two different mindsets, that you see in teachers.

I always get a little bit frustrated when there's particular schools or teachers asking like where's the curriculum? Or where's the scripted approach to doing this where I don't have to think about it? Like any of that could be created, but it wouldn't be empowering the students.

That's been one of my biggest fears. Let's just cram it into the existing paradigm and starve it to death.

Michael: I've reacted this way because I could not agree more. Yes. The number of times, especially early that we had to explain that at every level, right?

Dale: We'll buy the curriculum, like whatever.

The teachers that get it are the kind of teachers that want to do this kind of work. Again, if you can get maybe those two different mindsets to believe that but they want to be creative teachers, they want to be collaborative teachers, they want to be the exact things that they see the students doing. And that older model is neither of those.

Michael: I agree a hundred percent. So I'm not going to speak to that because you're all over it. And that's like I have to usually explain that to people. Yeah. And you're, you are articulating exactly exactly where we're at.

What we have found is, it's freeing, right? It's liberating. Thinking about if you have a clear why, like what is the point of the lab? If the point of the lab is not to leave having mastered every tool but is instead to leave, having cultivated the ability to learn, like I've learned how to learn. I've learned how to apply what I learned to actually solve problems, like actually make real solutions. If those are the things that I'm really driving at, then there's no existing curriculum that drives at those things. Curriculum are designed to drive at discreet skillsets.

If I want to be a master at 3D modeling and FDM printing, absolutely we can write that curriculum. I'm not situated to write that, but there are experts who can clearly put that together. But if the goal is to learn how to learn and solve meaningful problems and make discoveries about myself, that has to be an organic and fluid process.

And so like pulling teachers along, coaching teachers, really helping teachers understand that they're empowered to do it. Great teachers do this all the time. They do it instinctively, but traditionally, for one reason or another, systemically, we've not allowed them to do that. We've increasingly tried to, this is, I'll get on a soapbox so I'm not careful, but I think in education, especially in public education, but really in education in general for the last few decades is an effort to increase efficiency, we've standardized everything. But education isn't a factory. Like highly efficient education is probably poor education. It should be inefficient.

Dale: That's why we've lost a lot of hands-on learning in schools is because this is not efficient. It takes too much time. On another hand, your system that might be efficient, is it actually benefiting kids and are they learning?

Michael: Like efficient at what is an important question.

Dale: Efficient for the system to deliver it, but not necessarily productive.

Michael: Exactly. Exactly. I think that's a distinction that I'm just starting to toy with. And I love the kind of work that you all do and talk about because I do think there's a lot of conversations that should be had around the difference between productivity and efficiency in education. And anytime we're talking about human development, I get pretty anxious the moment we start talking about efficient models in human development, which is really what education's about.

Dale: I want more human models. What do we know about humans and how they learn and how they grow up. It's actually showing up. I think, one of the things they say about Covid is it's actually the social emotional learning of kids not being in groups. That is the real harm that's been done to them. You can make up the content pieces.

Michael: And amount of time we'll eventually learn how to read and do math.

Dale: It's a feeling sometimes that you don't belong. That this is difficult. I liked your thing-- I'm a different person than the other people around me. How do I adjust to that? And they, to me?

Blending Personalized Fabrication and Personalized Learning

Michael: Exactly. Like when Dr. Gershenfeld was starting some of the Fab Lab work and the how to make almost anything stuff in the late nineties, and he wrote a paper, I don't know, 97, 98, something like that, on, on personalized fabrication and a future look at the idea of personalized fabrication.

And certainly isn't my terminology, but the idea of like personalized learning comes along a few decades later. I'm thinking like we have the technology now to do personalized fabrication. This is a thing. We are thinking philosophically about personalized learning, but systemically we keep letting barriers pop up.

Locally, that's what I've been excited about is that the idea of blending the two, like what if you leveraged the ability to do personalized fabrication and married that with the idea of personalized learning and ignored the efficiency models of education. There's some amount of trust that you have to have there, but I trust teachers implicitly. Teachers are professionals and can really pull kids along, and we've been blessed to work with great teachers. That's probably why I feel that way, but I think that's probably true nationally.

Dale: One of the learnings maybe from the various reform efforts of the last 25 years is it was undermining teachers, really.

Michael: In my opinion. I agree. I couldn't agree more.

Dale: Listen, Michael let's stop there, just because this is a great conversation. We could go on for three hours and but I would love to stay in touch. I'd love to talk to you more to see if there are other things we could do together or I really love what you're doing.

I appreciate it and. Partly from the make side. This is important, the maker ed side as well. And trying to figure out what can we do to make more of this happen, and elevate it, get more kids involved, and as I said earlier, just in a level of just expanding the opportunity for kids to do more of this and for teachers to get involved and really feel part of it.

Michael: Absolutely. I appreciate that. Would love to stay connected. I couldn't agree more. For us, it's just truly about, we've seen the impact it's had on our community. Personally, I've seen the impact it's had on my own daughters. I think every kid deserves that. I want to find a way to do that.

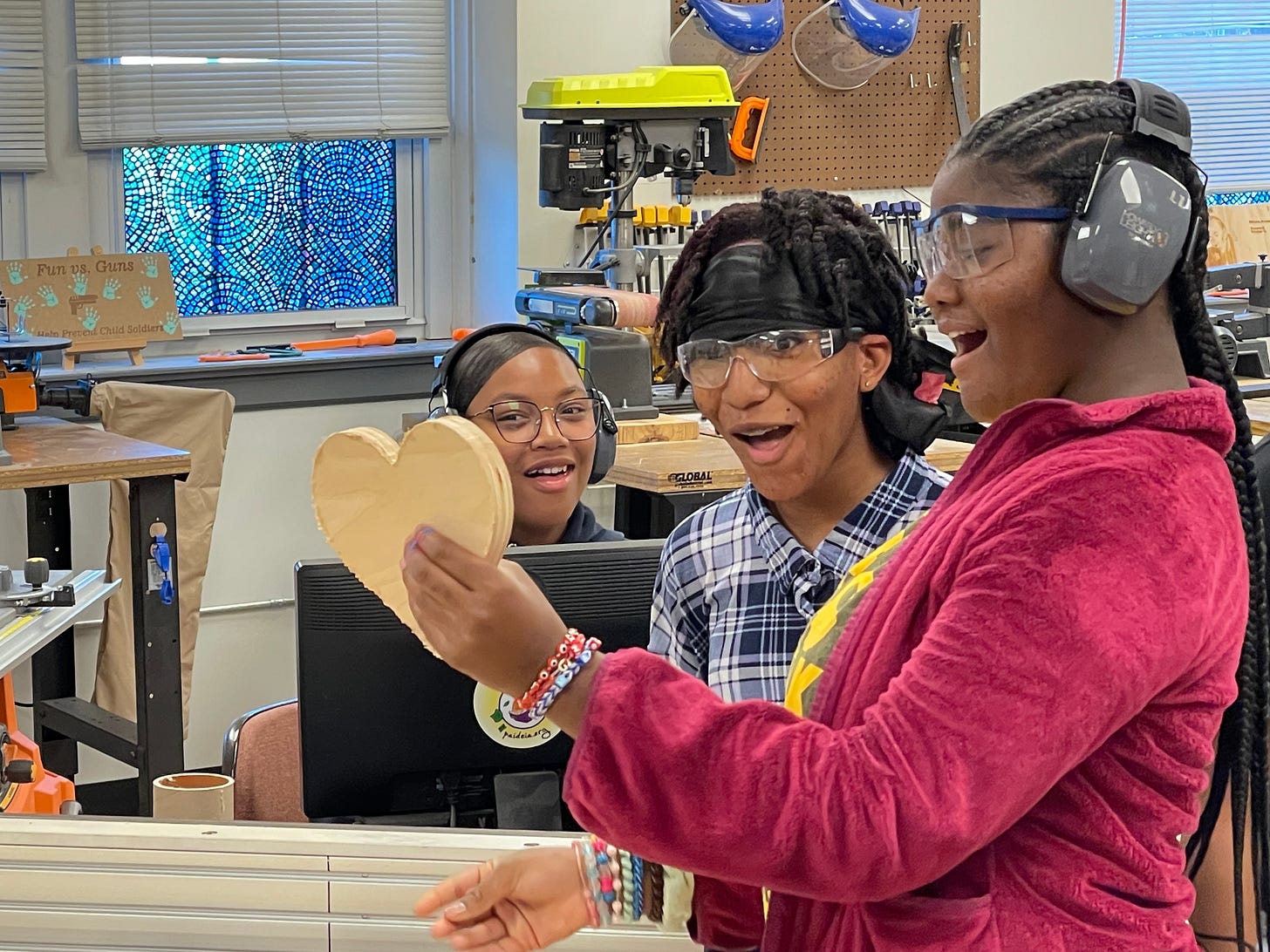

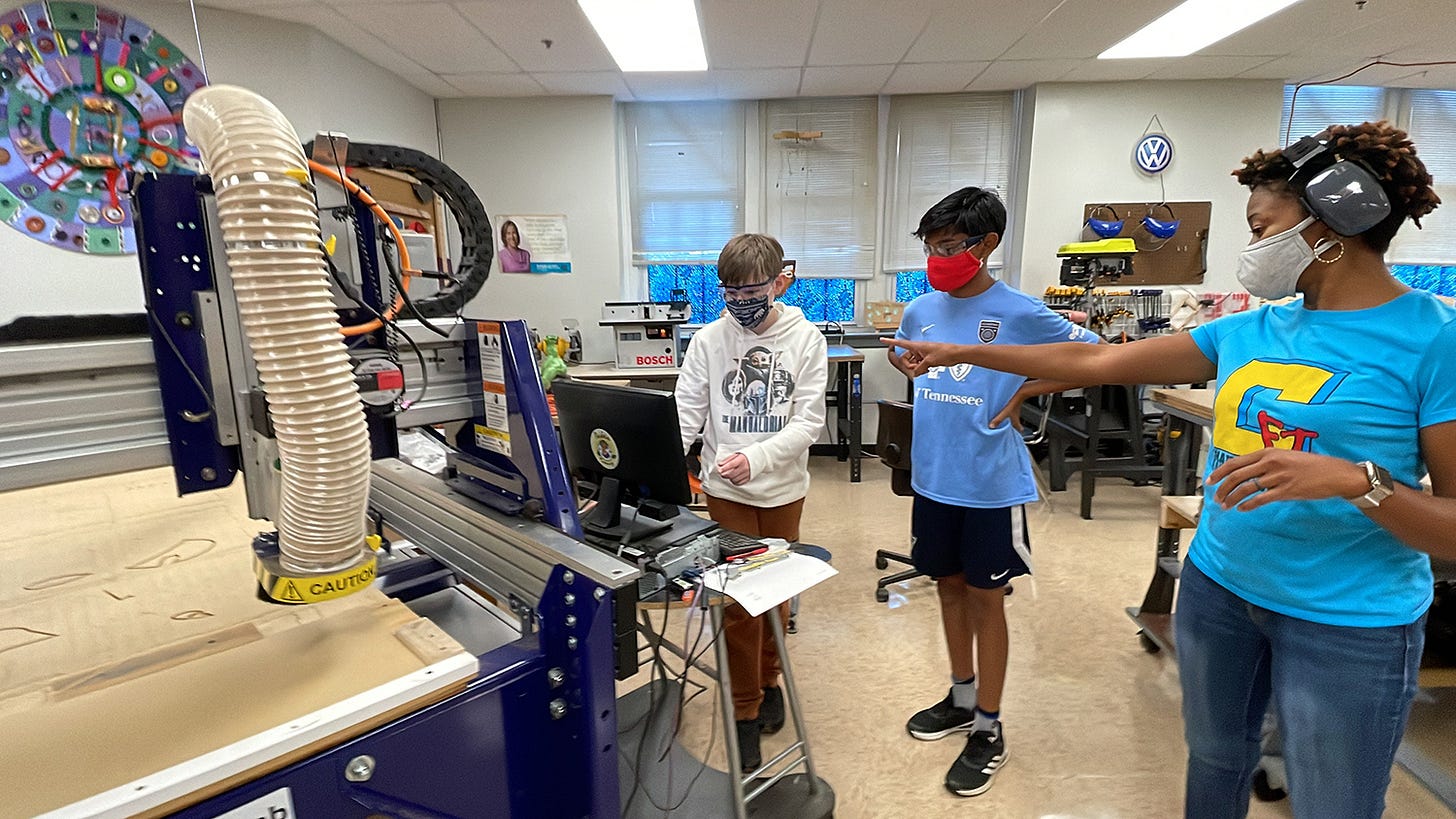

Photos from Michael Stone.